Human beings, unlike other animals, attend their dead and their corpses. This is attested since the Palaeolithic. The ways and customs of the various peoples referred to the fact of death and to treat the bodies, are many and varied. No doubt these rites are the result of confusion that causes death in all living beings; people seek immortality but man finds the decomposition of the body. It is therefore necessary to perform rites to avoid the process of decomposition . In expression of Walter Burkert, the Homo sapiens is a homo sepeliens (from Latin sepelio, burial), a man who buries his dead comrades.

In our cultural environment we are familiar with the burial, interment, inhumation (from Latin in, in, and humus, earth) and the cremation (from Latin cremationem, burning) or incineration (from Lat. in, on, and cinerem ,ash conversion, ash). Certainly cremation or incineration has grown since only a few decades in Spain. In ancient Greece and Rome both forms coexisted, in Greece cremation began to be practiced after the Mycenaean era; it was already in the second millennium BC on the Hittites, Hurrians or Troy VI.

Well, Herodotus, for example, offers an early reflection on the variety of rites and customs according the peoples, in a story referred to the Persians, whose empire was composed of diverse peoples. He tells us in his Histories, III, 38:

When Darius was king, he summoned the Greeks who were with him and asked them for what price they would eat their fathers' dead bodies. They answered that there was no price for which they would do it. Then Darius summoned those Indians who are called Callatiae, who eat their parents, and asked them (the Greeks being present and understanding through interpreters what was said) what would make them willing to burn their fathers at death. The Indians cried aloud, that he should not speak of so horrid an act. So firmly rooted are these beliefs; and it is, I think, rightly said in Pindar's poem that custom is lord of all. (translation by A. D. Godley)

And Cicero also provides an interesting text, Disputationes Tusculanae (Tusculan Disputations), I, XLV, 108:

But what occasion is there to animadvert on the opinions of individuals, when we may observe whole nations to fall into all sorts of errors? The Egyptians embalm their dead, and keep them in their houses ; the Pesians dress them over with wax, and then bury them, that they may preserve their bodies as long as possible. It is customary with the Magi to bury none of their order, unless they have been first torn by wild beasts. In Hyrcania, the people maintain dogs for the public use ; the nobles have their own — and we know that they have a good breed of dogs ; but every one, according to his ability, provides himself with some, in order to be torn by them ; and they hold that to be the best kind of interment. Chrysippus, who is curious in all kinds of historical facts, has collected many other things of this kind ; but some of them are lSo offensive as not to admit of being related. (Translated by C.C. Tonge).

Sed quid singulorum opiniones animadvertam, nationum varios errores perspicere cum liceat? Condiunt Aegyptii mortuos et eos servant domi. Persae etiam cera cirumlitos condunt, ut quam maxime permaneant diuturna corpora; Magorum mos est non humare corpora suorum nisi a feris sint ante laniata: inHyrcania plebs públicos alit canes, optimates domesticos: nobile autem genus canum illud esse, sed pro sua quisque facultate parat a quibus lanietur, eamque optimam, illi esse censent sepulturam. Permulta alia colligit Chrysippus, ut est in omni historia curiosus, sed ita taetra sunt quaedam, ut ea fugiat et reformidet oratio.

And Silius Italico, Punica, XIII, 466-487 says:

And Scipio replied : " Noblest scion of ancient Clausus,^ no business of my own (and I have heavy tasks to perform) shall take precedence of your request. ''All over the world the practice is different in this matter, and unlikeness of opinion produces various ways of burying the dead and disposing of their ashes. In the land of Spain, we are told (it is an ancient custom) the bodies of the dead are devoured by loathly vultures. When a king dies in Hyrcania, it is the rule to let dogs have access to the corpse. The Egyptians enclose their dead, standing in an upright position, in a cofHn of stone, and worship it ; and they admit a bloodless spectre to their banquets. '^ With the peoples of the Black Sea it is the custom to empty the skull by extracting the brain and to preserve the embalmed body for centuries. The Garamantes, again, dig a hole in the sand and bury the corpse naked, while the Nasamones in Libya commit their dead to the cruel sea for burial. Then the Celts have a horrid practice : they frame the bones of the empty skull in gold, and keep it for a drinking-cup. The Athenians passed a law, that the bodies of all who had fallen in battle in defence of their country should be burnt together on a single pyre. Again, among the Scythians the dead are fastened to tree-trunks and left to rot, and time at last is the burier of their bodies." (Translation by J.D. Duff)

Tunc iuuenis: ‘Gens o ueteris pulcherrima Clausi,

haud ulla ante tuam, quamquam non parua fatigent,

curarum prior extiterit. namque ista per omnis

discrimen seruat populos uariatque iacentum

exequias tumuli et cinerum sententia discors.

tellure, ut perhibent, (is mos anticus) Hibera

exanima obscenus consumit corpora uultur.

regia cum lucem posuerunt membra, probatum est

Hyrcanis adhibere canes. Aegyptia tellus

claudit odorato post funus stantia saxo

corpora et a mensis exanguem haud separat umbram.

exhausto instituit Pontus uacuare cerebro

ora uirum et longum medicata reponit in aeuum.

quid qui reclusa nudos Garamantes harena

infodiunt? quid qui saeuo sepelire profundo

exanimos mandant Libycis Nasamones in oris?

at Celtae uacui capitis circumdare gaudent

ossa, nefas, auro ac mensis ea pocula seruant.

Cecropidae ob patriam Mauortis sorte peremptos

decreuere simul communibus urere flammis.

at gente in Scythica suffixa cadauera truncis

lenta dies sepelit putri liquentia tabo.’

These are some interesting reflections for some diehards who do not respect customary way different of it from the group itself.

A curious rite, extended from east to west and also existed in some towns of the Iberian Peninsula, is the "exposure of corpses" to the carrion birds to be devoured and transported the deceased or his soul to heaven.

Exposing corpses to the carrion birds is attested in Catal Huyuk, archaeological site in modern Turkey that extends in time from the eighth millennium BC to 5,700 B.C. They buried their dead in their homes and how disjointed skeletons have suggested to the researchers that the corpses were exposed to birds and then collect the bones and bury them.

In any case it is a treat and a rite required by the Persian followers of Zoroaster in Iran and still practice today in India by Parsis, successors of Persian emigrants in the seventh century. (From Parsi home are for example the famous conductor Zubin Mehta and the equally famous actor Freddie Mercury; Parsis should be currently about 100000. All this and new requirements of the times make this rite "Parsi" adapt or go extinct, but in any case the rite continues to cause us deep impression.

The corpses are exposed into so-called "Towers of Silence" to be eaten by vultures and raised to heaven. They consider burying the dead pollutes the land, burning pollutes the air and fire, and throw to water pollutes the water.

Herodotus mentions the Persian funeral rite exposing corpses to the carrion on I, 140.

Apollonius of Rhodes in his curiosities plagued poem The Voyage of the Argonauts”, Singing III, (at number 200 ff) describes an different exposure of corpses because they are not offered to the vultures or scavenger birds :

and at once they passed forth from the ship beyond the reeds and the water to dry land, towards the rising ground of the plain. The plain, I wis, is called Circe's; and here in line grow many willows and osiers, on whose topmost branches hang corpses bound with cords. For even now it is an abomination with the Colchians to burn dead men with fire; nor is it lawful to place them in the earth and raise a mound above, but to wrap them in untanned oxhides and suspend them from trees far from the city. And so earth has an equal portion with air, seeing that they bury the women; for that is the custom of their land. (Translation by Seaton, R.C.)

Interestingly some ancient sources refer to the "exposure of corpses" to the carrion birds in ancient Iberia, Hispania.

Silius Italicus, speaking of the Celts who were mercenaries in the army of Anibal, says in Punica, III, 340-343:

The Celts who have added to their name that of

the Hiberi ^ came also. To these men death in battle

is glorious ; and they consider it a crime to burn the

body of such a warrior ; for they believe that the

soul goes up to the gods in heaven, if the body is

devoured on the field by the hungry vulture.

(Translation BY J. D. DUFF)

Venere et Celtae sociati nomen Hiberis.

his pugna cecidisse decus, corpusque cremari

tale nefas: caelo credunt superisque referri,

impastus carpat si membra iacentia uultur.

And soon after, as we have seen before, Silius Italicus: Punica, XIII, 471-472:

In the land of Spain, we are told (it

is an ancient custom) the bodies of the dead are devoured by loathly vultures.(TRANSLATION BY J. D. DUFF)

tellure, ut perhibent, (is mos anticus) Hibera

exanima obscenus consumit corpora uultur.

They so would practice a double ritual. Only the corpses of the killed in combat warriors would be exposed in some certain places to vultures to transporting her spirit to the heavens. Because they have that sacred function of carrier souls or spirits, they are named with the adjective of psychopomps (from Greek ψυχοπομπός, from ψυχή, psyche, soul, breath and πομπός, pompos, conductor).

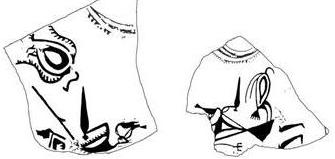

This practice is attested in several fragments of painted pottery of Numantia

It is saw In a fragment a vulture swooping down on a speared recumbent warrior with a sword in hand in the ground . In the other picture is already a vulture devouring the body of the warrior.

In the same Numantia, out of town, are found some stone circles which archaeologist consider possible expository for corpses in the manner of the "towers of silence" of Iranian Zoroastrians.

The rite clearly informs us about the sense of valor of the warrior and about the life understood in an agonistic and competitive mode and about contempt of death. It also reports a hope of reward in the hereafter where brave warriors live with the gods. This indicates the high ethical standards of these people.

There is a text of Aelian in De nat. Anim. X, 22 (FHA, VIII: 330) which extends the rite to the “vaccei” in Northern Plateau, Cantabrian neighbors:

“The “vacei”, people of Hesperia, burn in the fire the dead by disease, such as Feminil and cowardly dead, to highlight the ignominy of his death, whereas those who fell into a beautiful death, as brave and strong men and adorned with extraordinary value, the yield to be devoured by vultures, because they think that these birds are sacred”.

Aelian wrote in Greek but Friedrich Jacobs translated him into Latin in the modern Frommann edition, Jena, 1832 . He says like this:

Vaccaei, genus Hesperis, ex aliquo morbo mortuos, ut muliebriter et ignaviter defunctos, ad notandam mortis ignominiam igni cremant; eos vero, qui in bello morte occubuerunt, ut viros bonos et fortes, et eximia virtute ornatos, vulturibus devorandos objiciunt, quod eas aves sacras existiment.

But there are scholars who believe that reading the "vaccei" is a corrupt reading texts, which introduces a great doubt on the validity of the text. Actually the manuscripts of Aelianus say “barkaioi” but not “vacceoi”. The barkaioi are not known in the Iberian Peninsula. Barkaioi would would edited by Samuel Bochar (1599-1667) and then followed by other modern philologists and translated into Latin as baccaei and hence vacceoi. Maybe tell araouacoi, ie arévacoi, that some copyist cut into ara / ouakoi; ouakoi would bakoi. Ie, the original text also spoke of arevacoi. This interpretation, which is phonetically possible, would be consistent with the meaning of the text, because among the arevacoi of Numantia is well attested, as we said. The error is greatly strengthened by the absolute authority of Schulten for many years in the study of "Sources of ancient Hispania".

In any case they are numerous archaeological remains, paintings, inscriptions, tombstones which attest that in many places of the Iberian Peninsula, where may spread from the Celtibery .

So in the Vettons and Cantabria, as evidenced by the Cantabrian wake from Zurita (Renedo de Piélagos), very poor, in which seems a vulture pecking the corps of a recumbent warrior and another similar of Lara de los Infantes (Burgos), Binefar (Huesca), the Palao (Alcaniz, Teruel).

The rite is attested in various places in Europe in the Celts and Germans.

Pausanias tells us about the invasion of the Gauls in Greece commanded by Brennos in X, 21.6 that they left the corpses of the warriors fallen in the battles to scavenger birds.

After this battle at Thermopylae the Greeks buried their own dead and spoiled the barbarians, but the Gauls sent no herald to ask leave to take up the bodies, and were indifferent whether the earth received them or whether they were devoured by wild beasts or carrion birds. (Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A.,).

This scene of vultures devouring the corps of the warriors is sow , for example, in a glass of Faliscus, fourth century BC old.

In the Scandinavian Eddas we find numerous references to these beliefs, so in Edda Mayor, 1986: 33, 78.193-195, 199, 201-202, 212,217,225,246,255,259,297.

We can conclude, therefore, that the rite was practiced throughout the Celtic culture.

A similar ritual is found among some Indian tribes of North America which exhibit the corpses of his warriors on a sort of raised wooden stage; it sometimes appears in some western.

The rite is also attested in Tibet where the corpses are exposed in areas off the villages, where sometimes people help dismember the bodies.

Does this existing rite in different places have a common origin? quite possibly, if we think that the rite is lost in the mists of time, in prehistoric times, and the inhabitants of America came in several waves of Eurasia through the Bering Strait in the moments that could be traversed on foot.

After this long explanation we are able to understand a text in Longinus in On the Sublime, 3.2 in which he refers to to Gorgias of Leontines (483-375) and criticizes him because he names grandly called the vultures "living tombs ":

"So Gorgias of Leontines provokes laughter when he writes:" Xerxes ,Zeus of the Persians and vultures, living graves”.

If Gorgias knew the Persian custom, maybe the picture is not so grand. In any case it made a fortune in the story, used over and over again.

Shakespeare, for example, uses it in Macbeht in Act III, Scene fourth, 1359-1361:

Macbeth: If charnel-houses and our graves must send

Those that we bury back, our monuments 1360

Shall be the maws of kites.