Not today, but two thousand years ago certainly all roads led to Rome, which was the capital of a vast empire. More than 380 major roads or highways with more than 80,000 kms., allowed its legions, its officials, its citizens to go out and go easily to the capital, Rome. It is curious to note how the direction of all the roads marked to Rome as final destination, like rays or spokes of a huge circle. They range from the Pillars of Hercules in Hispania or from the “Hadrian’s Wall” in Scotland to the Euphrates in Mesopotamia, from northern Germany to the North African desert. Hence the saying that all roads lead to Rome.

These 380 main roads, (some scholars cite perhaps more accurately 372, which are relating by the Itinerarium Antonini, about later I will speak, 34 of them related to Hispania), which used to be called with the name of its promoter, were converging into each other up to the capital, Rome; nineteen enter into city: Salaria and Nomentana that came together within the Aurelian walls; Tiburtina, which joined the Collatina; the Praenestina and Labicana which joined other two; Latina; Appia; Sacra; Ardeatina which joined the Ostiensis coming from port; Septizonium; Portuensis; Aurelia which joined the Portuensis;and Flaminia.

Note: The roads also are called on Spanish “calzadas”, with a term of Vulgar Latin *calciāta, meaning paved road; “Calciata” derives from calx, cis, meaning limestone (in Spanish there are also calima, limestone, calcáreo, cálcico, calcium, and calcification, calcify, calcining, calculus and calculation from Latin “calculus”, small stone used for counting.. (see http://www.antiquitatem.com/en/roman-calculation-number-months-calculus )

The tracks are also called “viae stratae “, roads built with superimposed layers of different types of stone and gravel, which have made then eternal. Precisely from this name “stratae” derives the Italian “strada“, English street, German Straße, Dutch straat, Galician and Portuguese estrada.

A curiosity: the Spanish word “carretera” is derived from “carreta”, carriage, which perhaps is not Latin but originally a Celtic word, “car“. This brings us to the consideration of the importance of the “Celtic substrate” in many of the territories controlled by Rome. Moreover, the “Celtic” is closely related to the Latin because both are Indo-European languages. Precisely the Indo-European root word could be “* kers”, which also derived or is related to currere (run), cursus, course, …

Note: I will say today, as a curiosity, that one of the most famous in Spain, used or maintained even today in many places, is known as “Via de la Plata“, which goes from Mérida (Augusta Emerita) to Astorga (Asturica Augusta ), whose name has nothing to do with the mineral so prized in the ancient world, the Latin “Argentum“, Spanish “plata”, English silver), a name that surely will remind the reader some derivatives (silver-plated, argentiferous...). The name “via de la Plata” derives from the Arabic name in the Andalusian era “via al-Balat,” paved road.

Well, in this huge network the routes were marked with landmarks or cairns marking distances and remembering the authors or promoters of the road for their greater honor and glory. These milestones were called “milliariums ” because they were placed every thousand steps (one mile equals approximately 1481 meters), as today they are placed kilometers stones every thousand meters when we apply the metric system.

Milliariums of city of Carcaboso, (Cáceres, Spain)

Because the roads or highways depart from or arrive to Rome like the spokes of a huge circle, it was there placed the milestone “0” as a focal point, like now it exists in the Puerta del Sol in Madrid (Spain) the famous Kilometer “0”, from where all the radial roads go to the corners of Spain.

It is curious to note how centralized states had in antiquity, as today have, a radial arrangement and structure: to go from one city to another it is necessary to go through the center, where all paths converge.

That Roman milestone (milliarium) was not really named “0” (zero), because the Romans did not handle zero, but to emphasize the central importance they called it milliarium aureum, gold milestone, because it was made of gold-plated bronze, and it was placed in the Forum, together the Temple of Saturn, by Augustus in 20 BC. It should have 3.45 meters high and the column 1.15 diameter.

Distances are measured on reference to it. The inscription on that column is not known, perhaps there were only the emperor Augustus name or the names of the major cities of the Empire and the distances, as numerous authors assume with no sufficient basis ,influenced by current customs, or perhaps there were the names of the keepers of the road network, ther “curatores viarum”.

Cassius Dio remembers how Augustus was named “curator viarum” and he ordered to erect the milliarium aureum, coinciding with the celebration of his triumph over the Parthians:

Cassius Dio, 54,8,4

Now all this was done later in commemoration of the event; but at the time of which we are speaking he was chosen commissioner of all the highways in the neighbourhood of Rome, and in this capacity set up the golden mile-stone, as it was called, and appointed men from the number of the ex-praetors, each with two lictors, to attend to the actual construction of the roads. (translated by Earnest Cary)

The phrase “All roads lead to Rome” perhaps was created at the time where this column, this milestone was erected.

We have also quotes of Plutarch, Galba 24.4; Pliny, Naturalis Historia 3.66; Tacitus, Historiae 1.27; Suetonius, Otho 6.2.

Plutarch also makes a reference to the milestone as the end point of all Roman roads at the time that Otto is about to be named emperor to replace Galba:

Plutarch, Galba 24.4

Thus Otho had even been discovered by the finger of the god; being there just behind Galba, bearing all that was said, and seeing what was pointed out to them by Umbricius. His countenance changed to every colour in his fear, and he was betraying no small discomposure, when Onomastus, his freedman, came up and acquainted him that the master builders had come, and were waiting for him at home. Now that was the signal for Otho to meet the soldiers. Pretending then that he had purchased an old house, and was going to show the defects to those that had sold it to him, he departed; and passing through what is called Tiberius’s house, he went on into the forum, near the spot where a golden pillar stands, at which all the several roads through Italy terminate. (Translated by John Dryden)

Tacitus on Stories 1.27 and Suetonius on live of Otto, 6, tell us the same episode and also they refer to the golden milestone.

Also Pliny the Elder, who offers extensive information on routes and cities, makes an interesting reference on a text which increases the size and importance of Rome city unparalleled in the world.

Pliny, Naturalis Historia, III, 66-67

Romulus left the city of Rome, if we are to believe those who state the very greatest number, having three gates and no more. When the Vespasians were emperors and censors, in the year from its building 826, the circumference of the walls which surrounded it was thirteen miles and two-fifths. Surrounding as it does the Seven Hills, the city is divided into fourteen districts, with 265 cross-roads under the guardianship of the Lares. If a straight line is drawn from the mile-column placed at the entrance of the Forum, to each of the gates, which are at present thirty-seven in number (taking care to count only once the twelve double gates, and to omit the seven old ones, which no longer exist), the result will be [taking them altogether], a straight line of twenty miles and 765 paces. But if we draw a straight line from the same mile-column to the very last of the houses, including therein the Prætorian encampment, and follow throughout the line of all the streets, the result will then be something more than seventy miles. Add to these calculations the height of the houses, and then a person may form a fair idea of this city, and will certainly be obliged to admit that there is not a place throughout the whole world that for size can be compared to it. (John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S., H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A., Ed)

Plin. Nat. 3.30 (o 3.66-67)

Urbem tris portas habentem Romulus reliquit aut, ut plurimas tradentibus credamus, IIII. moenia eius collegere ambitu imperatoribus censoribusque Vespasianis anno conditae DCCCXXVI m. p. XIII:CC, conplexa montes septem. ipsa dividitur in regiones XIIII, compita Larum CCLXV, eiusdem spatium mensura currente a miliario in capite Romani fori statuto ad singulas portas, quae sunt hodie numero XXXVII, ita ut XII portae semel numerentur praetereantur ex veteribus VII, quae esse desierunt, efficit passuum per directum XX:M:DCCLXV. ad extrema vero tectorum cum castris praetoriis ab eodem miliario per vicos omnium viarum mensura colligit paulo amplius LX p. quod si quis altitudinem tectorum addat, dignam profecto aestimationem concipiat fateaturque nullius urbis magnitudinem in toto orbe potuisse ei comparari.

We have lots of information on the Roman roads and its design, not only in texts but also as the result of archaeological studies. There are two documents which I will try another time, which are particularly important: the Itinerarium Antonini, Itinerary of Antoninus and Tabula Peuntingeriana.

The Itinerarium Provinciarum Antonini Augusti is a book or road guide made in the early third century of Christ (217) in which the military roads of the time of Caracalla were related, giving account of the cities and mansions , similar to our service areas, and distances between them. The current document is based on a copy of the fourth century and modern first published in 1521.

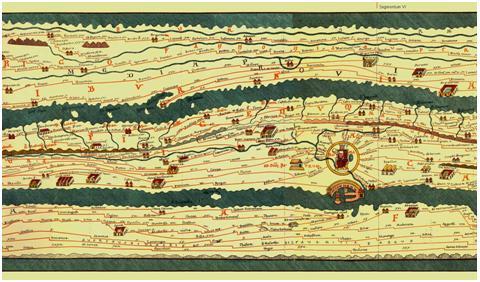

The second document, the Tabula Peutingeriana, is a kind of map or schema or plan picture that includes the main roads, indicating the cities and stops each from India to Britain. Unfortunately it is missed the part referring to Spain, which must be supplemented with the Itinerarium Antonini. A copy of the twelfth century of a document from IV or V century is conserved, although it could be made earlier. The current document is kept in Vienna Nationalbibliotek, and covers an area of 6.8 meters long by 33 cm. wide divided into 12 sheets. It is named from Konrad Peutinger, the German humanist who discovered it.

The photograph shows the V and VI segments where of the Tabula Peutingeriana, where it is represented Italy with the capital Rome, between the Adriatic and the Mediterranean Sea.

Other authors, Pliny the Elder and Strabo, give us lots of information about roads and cities through which they pass.

So the sentence “all roads lead to Rome” would have at that time a real and geographical sense. We can assume, then, that the inhabitants of the Empire, from Mesopotamia to Britain, from Germany to the African desert, would pronounce often in Latin the phrase “omnes viae ducunt Romam” as today is still done in all Western languages since its appearance.

I said that “we can assume” because it is not witnessed the Latin phrase quoted in any document of ancient times. But the assumption is reasonable if Roma appealed to citizens around the world and the “maps” of the time have Rome as a point of departure and to arrival and it is noted the central focus whit all Roman greatness with the famous golden milestone (milliarium aureum).

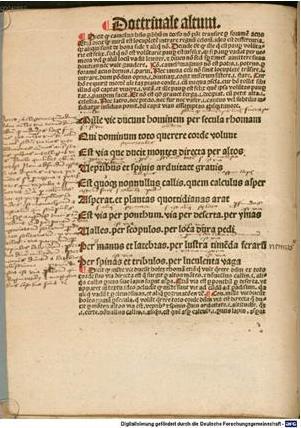

According to our knowledge today, the sentence is written first time in the Middle Ages, about the year 1175, on a text by Alain de Lille, (Alanus ab Insulis in Latin), (c 1128 -. 1202/1203). Alain de Lille wrote numerous works, the most famous of moral content. He wrote the entitled Liber Parabolarum, Book of parables. On Chapter V is where the aforementioned phrase is, not exactly as I have presented it, but as Mille viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam (A thousand roads lead men forever to Rome).

Note: Note the acuity of Alain de Lille for translate his name into Latin: it is evident that Alanus comes from Alain, but in the case of the name “de Lille” he makes a curious phonetic play: as “Lille“, the name of the French town in north Frances, sounds in French like “de l’île, “the island, he translated it into Latin as” ab Insulis “,” from the Islands “.

Alain de Lille (Alanus ab insulis) entitled one of his “moralizing fables” in chapter V:

Mille viae ducunt hominem per saecula Romam

A thousand roads lead men forever to Rome.

The title appears in the print edition of Leipzig 1499 whose photograph I offer; so it was not done in previous editions as one of Cologne 1497. I do not know how it appears in the oldest manuscripts. But in any case, he uses the above expression and a similar comment or explanation in his parable multae viae ducunt hominem romam (Many roads lead man to Rome) and also mille viae ducunt rhomines romam per saecula (a thousand roads lead men forever to Rome). (Mille viae ducunt homines Romam per saecula: qui volunt quaerere toto corde dominum: via est directa quae …)

I present the complete parable, in which the sentence has a figurative sense, of the thousands it may have and which is still used in any current context.

A thousand roads lead men forever to Rome

For those who want to seek the Lord with all your heart

There is a path that leads directly over to the top of the mountains

with its slopes full of brambles and thorns.

And also a footpath that rough stone makes rough

and scrapes every day the soles of the feet.

There is also a path across the sea, a path across the wilderness,

across deep valleys, between rocks, across hard places for feet.

Across forests and hidden places, across places which fearsome beasts walk,

among thorns and thistles, across muddy places.

Mille viae ducunt hominem per saecula Romam

Qui dominum toto quaerere corde volunt

Est via quae ducit montes directa per altos

Vepribus et spinis arduitate gravis

Est quoque nonnullus callis. quem calculus asper

Asperat. et plantas quotidianas arat

Est via per pontum. via per deserta. per imas

Valles. per scopulos. per loca dura pedi

Per nemus et latebras. per lustra timenda ferarum

Per spinas tribulos. per luculenta vaga

Scanned by Münchener Digitalisierungszentrum

The figurative sense is obvious: there are many roads leading to the Lord, to Paradise, for people who seek him with all your heart, similar than there were many roads which lead to Rome. That is, you can reach a certain purpose in many ways, different paths can take one to the same goal

On English he is Geoffrey Chaucer who uses the proverb first time in his Astrolabe of 1391, where the proverb appears as “right as diverse pathes leden diverse folk the righte way to Rome”.

The Swiss germanist Samuel Singer includes the sentence in his Thesaurus Proverbiorum Medii Aevi: Lexikon der Sprichwörter des Romanisch-Germanischer Mittelalters in the word Rom.

Another time day I will talk about building and factory of roads, meanwhile I offer a curious link to a curious page that provides information about the distance from any point of empire to Rome by the Roman roads of Tabula Peutingeriana and Itinerarium Antonini: http://http://www.omnesviae.org/.