It is difficult to escape the celebration of “Valentine’s Day, the lovers day.” A powerful tradition that has its roots in antiquity and in the Middle Ages and is currently anchored by the commercial interests of powerful corporations and business organizations, seems to prevail unchecked.

The matter is not without interest but I have to leave for another time to dig a little on the origin of the holiday, in the absence of the martyr Saint Valentine or of powerful arguments to doubt his existence, in the Christianization of a party of most important pagan holidays of February, the Lupercalia.

All this is of great interest, but I prefer to postpone its study. I want to limit myself now to tell one of the most beautiful love stories of antiquity that Ovid tells in his Metamorphoses, the tragic love story of Pyramus and Thisbe, two dead lovers by a tragic error.

The story, the tale, well known since Antiquity, was so successful since the Renaissance that it is but one from which seems to emerge the most famous tragedy of Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, who also used it on A Midsummer Night's Dream.

It is true that Hyginus, contemporary although a little older than Ovid, (64 BC -. 17) makes a simple reference to the story of Pyramus and Thisbe in his Fables Hyginus is a writer from Valencia, (Spain) according to Luis Vives, although others scholars doubt the place of his birth.

(See http://www.antiquitatem.com/en/moon-sun-eclipse-antikythera-mechanism )

He says in Fables, CCXLII:

…..Pyramus in Babylonia ob amorem Thisbes ipse se occidit…

Pyramus in Babylonia out of love for Thisbe killed himself.

CCXLII Qui se ipsi interfecerunt

CCXLIII Thisbe Babylonia propter Pyramum quod ipse se interfecerat.

Thisbe of Babylon killed herself because Pyramus had killed himself.

CCXLIII Quae se ipsae interfecerunt

But he is the poet Ovid who tells this story in Book IV of his work Metamorphoses. We know of no author who told in advance and there are few who do later, some with some variation.

The story is certainly of oriental origin, as evidenced its location in Babylon. Certainly since Ovid the story had remarkable success and was well known; before it seems that it was not known, judging by the words of Ovid: "vulgaris fabula non est" "it is not a popular story." In Late Antiquity there is a slightly different version of Nonnus, Latin author of the late IV or early of V century, in his Dyonisiaca XII, 84 et seq. He places it in Cilicia, not in Babylon.

Augustine presents us as one of the common themes that students have to develop as an exercise in studying rhetoric, which means that the issue was already well known. So he says, referring to the wall interposed between Pyramus and Thisbe in his On Order, De ordine, 1,3,8:

I tell you, that I irritate myself when I see you singing and suffering with these verses of all kinds that stand between you and the truth a wall thicker than this one they strove to raise between your lovers; but they were connected by a hairline crack. He tried then to sing Pyramus).

Irritor, inquam, abs te versus istos tuos omni metrorum genere cantando et ululando insectari, qui inter te atque veritatem immaniorem murum quam inter amantes tuos conantur erigere”. ; nam in se illi vel inolita rimula respirabant. Pyramum enim ille tum canere instituerat.

And then in the same De Ordine, 1,5,12

I tell you: so be it that you call me an irritating busybody; for surely I can not but be irritating if I have attack you when you talked with Pyramus and Thisbe …

Cui ego licet, inquam, me odiosum percontatorem voces; vix enim possum non esse,qui expugnavi me cum Pyramo et Thisbe coloqueris

In the Middle Ages it is commonplace as reference to "unhappy love". The myth appears in all medieval European literature: in Spain and appears in The Fazienda overseas, probably in the year 1153. In France there are numerous examples; it is sufficient the Chretien de Troyes in his Conte of Charrette. Chaucer in England told the story in his The Legend of Good Women. In Italy, Boccaccio summarizes the fable in his De claris mulieribus, although the names of Pyramus and Thisbe not appear.

In Spain it has a minor presence in the Middle Ages by the general lack of Ovid, but it seems that the Marquis de Santillana and Gomez Manrique had a translation of the Metamorphoses. But since the Renaissance there are dozens poets and literary authors who replicate the legend, of which are also numerous fictional romances that were sung in Spain and Portugal. Numerous editions and translations of Ovid from the Renaissance facilitated the direct relationship between authors and this legend.

I want to emphasize only two of Spanish authors without going into the matter, because my interest at the moment is to provide readers with direct text of Ovide; so they can enjoy an exciting literary narrative. These two authors are Cervantes, who in his Don Quixote makes three references to the unhappy love affair: the story of Cardenio and Lucinda in First Part (I, 23-24), and in the Second the sonnet of Lorenzo Miranda, son of The Knight of the Green Gaban, (II, 16-18) and the episode of the Wedding of Camacho (II, 19,20 and 21) with the comic inversion of the fatal love.

I offer the Miranda’s Lorenzo sonnet, because it is shorter:

The lovely maid, she pierces now the wall;

Heart-pierced by her young Pyramus doth lie;

And Love spreads wing from Cyprus isle to fly,

A chink to view so wondrous great and small.

There silence speaketh, for no voice at all

Can pass so strait a strait; but love will ply

Where to all other power 'twere vain to try;

For love will find a way whate'er befall.

Impatient of delay, with reckless pace

The rash maid wins the fatal spot where she

Sinks not in lover's arms but death's embrace.

So runs the strange tale, how the lovers twain

One sword, one sepulchre, one memory,

Slays, and entombs, and brings to life again.

(Translated by John Ormsby)

El muro rompe la doncella hermosa

que de Píramo abrió el gallardo pecho;

parte el Amor de Chipre y va derecho

a ver la quiebra estrecha y prodigiosa.

Habla el silencio allí, porque no osa

La voz entrar por tan estrecho estrecho;

las almas sí, que amor suele de hecho

facilitar la más difícil cosa

Saltó el deseo de compás y el paso

de la imprudente virgen solicita

por su gusto su muerte. Ved qué historia;

Que a entrambos en un punto, ¡oh extraño caso!,

los mata, los encubre y resucita

una espada, un sepulcro, una memoria.

The other is Gongora, who wrote the story, albeit humorous, or to be more precise, difficult to interpret, that is now known as the Enlightenment and Defense of the Fable of Pyramus and Thisbe (1618). Gongora had previously alluded to the theme of Pyramus and Thisbe in one of the Letrillas (a brief poem) in which the popular refrain 'let me go warm and the people may laugh” is repeated.

Because love is so cruel

that thalamus makes a sword

of Pyamus and his love,

where he and she together are,

let be my Tisbe a cake

and let be the sword my tooth

and the people may laugh

Pues amor es tan cruel

que de Píramo y su amada

hace tálamo una espada,

do se junten ella y él,

sea mi Tisbe un pastel

ya la espada sea mi diente

y ríase la gente.

Shakespeare, meanwhile, recalls the story in the famous tragedy Romeo and Juliet and with an ironic tone in "A Midsummer Night's Dream", though specialists say that the English author does not was directly influenced by the work of Ovid, but the influence came indirectly from Italian authors from the poem by Arthur Brooke the Tragical Historye of Romeus and Juliet and from translation of William Painter "Rhomeo and Julietta"; these authors made use of a French version of Pierre Boaiastou which was based on Romeo and Giuletta of Mateo Bandello and a Giulietta e Romeo of Luigi da Porto.

But Shakespeare would have no difficulty in knowing such a popular topic in Europe: Golding had had translated the Metamorphoses in 1567.

Of course the issue was relevant to other artists in addition to the letters, as painters and musicians, from ancient times to the present day.

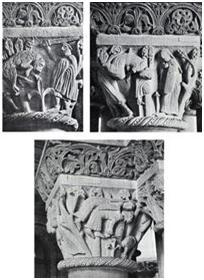

I offer only four examples of paintings on the theme: A first-century Pompeii, one from a twelfth-century Romanesque capital in Basel, one of the XVIII-XIX and one absolutely contemporary.

Pyramus and Thisbe represented in a fresco of the House of Octavius Cuartio (Pompeii). S. I d.C.

Cloister of the Cathedral of Basel, late twelfth century, (with a Christian moralizing interpretation)

Pierre-Claude Gautherot, (1769-1825),

Gabriel Alonso, painting published by the digital publishing One and Zero (http://unoyceroediciones.com/)

Examples of music go from opera A Midsummer Night's Dream, by Benjamin Britten based on A Midsummer Night's Dream or West Side Story based on Romeo and Juliet to the adaptation of the Beatles, in which Paul McCartney was Pyramus, Thisbe was John Lennon, George Harrison was the Moon and Ringo Starr was the lion.

But enough of much scholarly considerations and inconsequential curiosities and let us allow the poet Ovid to relate in detail the unfortunate history.

Metamorphoses, IV, 42…..54; 55-166

it pleased her sisters, and they ordered her

to tell the story that she loved the most.

So, as she counted in her well-stored mind

the many tales she knew, first doubted she

whether to tell the tale of Derceto,—

that Babylonian, who, aver the tribes

of Palestine, in limpid ponds yet lives,—

her body changed, and scales upon her limbs;

…..

or of that tree

which sometime bore white fruit, but now is changed

and darkened by the blood that stained its roots.—

Pleased with the novelty of this, at once

she tells the tale of Pyramus and Thisbe;—

and swiftly as she told it unto them,

the fleecy wool was twisted into threads.

PYRAMUS AND THISBE

When Pyramus and Thisbe, who were known

the one most handsome of all youthful men,

the other loveliest of all eastern girls,—

lived in adjoining houses, near the walls

that Queen Semiramis had built of brick

around her famous city, they grew fond,

and loved each other—meeting often there—

and as the days went by their love increased.

They wished to join in marriage, but that joy

their fathers had forbidden them to hope;

and yet the passion that with equal strength

inflamed their minds no parents could forbid.

No relatives had guessed their secret love,

for all their converse was by nods and signs;

and as a smoldering fire may gather heat,

the more 'tis smothered, so their love increased.

Now, it so happened, a partition built

between their houses, many years ago,

was made defective with a little chink;

a small defect observed by none, although

for ages there; but what is hid from love?

Our lovers found the secret opening,

and used its passage to convey the sounds

of gentle, murmured words, whose tuneful note

passed oft in safety through that hidden way.

There, many a time, they stood on either side,

thisbe on one and Pyramus the other,

and when their warm breath touched from lip to lip,

their sighs were such as this: “Thou envious wall

why art thou standing in the way of those

who die for love? What harm could happen thee

shouldst thou permit us to enjoy our love?

But if we ask too much, let us persuade

that thou wilt open while we kiss but once:

for, we are not ungrateful; unto thee

we own our debt; here thou hast left a way

that breathed words may enter loving ears.,”

so vainly whispered they, and when the night

began to darken they exchanged farewells;

made presence that they kissed a fond farewell

vain kisses that to love might none avail.

When dawn removed the glimmering lamps of night,

and the bright sun had dried the dewy grass

again they met where they had told their love;

and now complaining of their hapless fate,

in murmurs gentle, they at last resolved,

away to slip upon the quiet night,

elude their parents, and, as soon as free,

quit the great builded city and their homes.

Fearful to wander in the pathless fields,

they chose a trysting place, the tomb of Ninus,

where safely they might hide unseen, beneath

the shadow of a tall mulberry tree,

covered with snow-white fruit, close by a spring.

All is arranged according to their hopes:

and now the daylight, seeming slowly moved,

sinks in the deep waves, and the tardy night

arises from the spot where day declines.

Quickly, the clever Thisbe having first

deceived her parents, opened the closed door.

She flitted in the silent night away;

and, having veiled her face, reached the great tomb,

and sat beneath the tree; love made her bold.

There, as she waited, a great lioness

approached the nearby spring to quench her thirst:

her frothing jaws incarnadined with blood

of slaughtered oxen. As the moon was bright,

Thisbe could see her, and affrighted fled

with trembling footstep to a gloomy cave;

and as she ran she slipped and dropped her veil,

which fluttered to the ground. She did not dare

to save it. Wherefore, when the savage beast

had taken a great draft and slaked her thirst,

and thence had turned to seek her forest lair,

she found it on her way, and full of rage,

tore it and stained it with her bloody jaws:

but Thisbe, fortunate, escaped unseen.

Now Pyramus had not gone out so soon

as Thisbe to the tryst; and, when he saw

the certain traces of that savage beast,

imprinted in the yielding dust, his face

went white with fear; but when he found the veil

covered with blood, he cried; “Alas, one night

has caused the ruin of two lovers! Thou

wert most deserving of completed days,

but as for me, my heart is guilty! I

destroyed thee! O my love! I bade thee come

out in the dark night to a lonely haunt,

and failed to go before. Oh! whatever lurks

beneath this rock, though ravenous lion, tear

my guilty flesh, and with most cruel jaws

devour my cursed entrails! What? Not so;

it is a craven's part to wish for death!”

So he stopped briefly; and took up the veil;

went straightway to the shadow of the tree;

and as his tears bedewed the well-known veil,

he kissed it oft and sighing said, “Kisses

and tears are thine, receive my blood as well.”

And he imbrued the steel, girt at his side,

deep in his bowels; and plucked it from the wound,

a-faint with death. As he fell back to earth,

his spurting blood shot upward in the air;

so, when decay has rift a leaden pipe

a hissing jet of water spurts on high.—

By that dark tide the berries on the tree

assumed a deeper tint, for as the roots

soaked up the blood the pendent mulberries

were dyed a purple tint.

Thisbe returned,

though trembling still with fright, for now she thought

her lover must await her at the tree,

and she should haste before he feared for her.

Longing to tell him of her great escape

she sadly looked for him with faithful eyes;

but when she saw the spot and the changed tree,

she doubted could they be the same, for so

the colour of the hanging fruit deceived.

While doubt dismayed her, on the ground she saw

the wounded body covered with its blood;—

she started backward, and her face grew pale

and ashen; and she shuddered like the sea,

which trembles when its face is lightly skimmed

by the chill breezes;—and she paused a space;—

but when she knew it was the one she loved,

she struck her tender breast and tore her hair.

Then wreathing in her arms his loved form,

she bathed the wound with tears, mingling her grief

in his unquenched blood; and as she kissed

his death-cold features wailed; “Ah Pyramus,

what cruel fate has taken thy life away?

Pyramus! Pyramus! awake! awake!

It is thy dearest Thisbe calls thee! Lift

thy drooping head! Alas,”—At Thisbe's name

he raised his eyes, though languorous in death,

and darkness gathered round him as he gazed.

And then she saw her veil; and near it lay

his ivory sheath—but not the trusty sword

and once again she wailed; “Thy own right hand,

and thy great passion have destroyed thee!—

And I? my hand shall be as bold as thine—

my love shall nerve me to the fatal deed—

thee, I will follow to eternity—

though I be censured for the wretched cause,

so surely I shall share thy wretched fate:—

alas, whom death could me alone bereave,

thou shalt not from my love be reft by death!

And, O ye wretched parents, mine and his,

let our misfortunes and our pleadings melt

your hearts, that ye no more deny to those

whom constant love and lasting death unite—

entomb us in a single sepulchre.

“And, O thou tree of many-branching boughs,

spreading dark shadows on the corpse of one,

destined to cover twain, take thou our fate

upon thy head; mourn our untimely deaths;

let thy fruit darken for a memory,

an emblem of our blood.” No more she said;

and having fixed the point below her breast,

she fell on the keen sword, still warm with his red blood.

But though her death was out of Nature's law

her prayer was answered, for it moved the Gods

and moved their parents. Now the Gods have changed

the ripened fruit which darkens on the branch:

and from the funeral pile their parents sealed

their gathered ashes in a single urn.

So ended she; at once Leuconoe

took the narrator's thread; and as she spoke

her sisters all were silent.

(Translation from Ovid, Metamorphoses. Brookes More. Boston. Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922).

Dicta probant primamque iubent narrare sorores.

Illa, quid e multis referat (nam plurima norat),

cogitat et dubia est, de te, Babylonia, narret,

Derceti, quam versa squamis velantibus artus

stagna Palaestini credunt motasse figura;

……

an, quae poma alba ferebat,

ut nunc nigra ferat contactu sanguinis arbor.

Hoc placet, hanc, quoniam vulgaris fabula non est,

talibus orsa modis, lana sua fila sequente:

…..

55-168

Pyramus et Thisbe.

“Pyramus et Thisbe, iuvenum pulcherrimus alter,

altera, quas oriens habuit, praelata puellis,

contiguas tenuere domos, ubi dicitur altam

coctilibus muris cinxisse Semiramis urbem.

Notitiam primosque gradus vicinia fecit:

tempore crevit amor. Taedae quoque iure coissent:

sed vetuere patres. Quod non potuere vetare,

ex aequo captis ardebant mentibus ambo.

Conscius omnis abest: nutu signisque loquuntur,

quoque magis tegitur, tectus magis aestuat ignis.

Fissus erat tenui rima, quam duxerat olim,

cum fieret paries domui communis utrique.

Id vitium nulli per saecula longa notatum

(quid non sentit amor?) primi vidistis amantes,

et vocis fecistis iter; tutaeque per illud

murmure blanditiae minimo transire solebant.

Saepe, ubi constiterant hinc Thisbe, Pyramus illinc,

inque vices fuerat captatus anhelitus oris,

“invide” dicebant “paries, quid amantibus obstas?

quantum erat, ut sineres toto nos corpore iungi,

aut hoc si nimium est, vel ad oscula danda pateres?

Nec sumus ingrati: tibi nos debere fatemur,

quod datus est verbis ad amicas transitus aures.”

Talia diversa nequiquam sede locuti

sub noctem dixere ”vale” partique dedere

oscula quisque suae non pervenientia contra.

Postera nocturnos aurora removerat ignes,

solque pruinosas radiis siccaverat herbas:

ad solitum coiere locum. Tum murmure parvo

multa prius questi, statuunt, ut nocte silenti

fallere custodes foribusque excedere temptent,

cumque domo exierint, urbis quoque tecta relinquant;

neve sit errandum lato spatiantibus arvo,

conveniant ad busta Nini lateantque sub umbra

arboris. Arbor ibi, niveis uberrima pomis

ardua morus, erat, gelido contermina fonti.

Pacta placent. Et lux, tarde discedere visa,

praecipitatur aquis, et aquis nox exit ab isdem.

Callida per tenebras versato cardine Thisbe

egreditur fallitque suos, adopertaque vultum

pervenit ad tumulum, dictaque sub arbore sedit.

Audacem faciebat amor. Venit ecce recenti

caede leaena boum spumantes oblita rictus,

depositura sitim vicini fontis in unda.

Quam procul ad lunae radios Babylonia Thisbe

vidit et obscurum timido pede fugit in antrum,

dumque fugit, tergo velamina lapsa reliquit.

Ut lea saeva sitim multa conpescuit unda,

dum redit in silvas, inventos forte sine ipsa

ore cruentato tenues laniavit amictus.

Serius egressus vestigia vidit in alto

pulvere certa ferae totoque expalluit ore

Pyramus: ut vero vestem quoque sanguine tinctam

repperit, “una duos” inquit “nox perdet amantes.

E quibus illa fuit longa dignissima vita,

nostra nocens anima est: ego te, miseranda, peremi,

in loca plena metus qui iussi nocte venires,

nec prior huc veni. Nostrum divellite corpus,

et scelerata fero consumite viscera morsu,

o quicumque sub hac habitatis rupe, leones.

Sed timidi est optare necem.” Velamina Thisbes

tollit et ad pactae secum fert arboris umbram;

utque dedit notae lacrimas, dedit oscula vesti,

“accipe nunc” inquit “nostri quoque sanguinis haustus!”

quoque erat accinctus, demisit in ilia ferrum,

nec mora, ferventi moriens e vulnere traxit.

Ut iacuit resupinus humo: cruor emicat alte,

non aliter quam cum vitiato fistula plumbo

scinditur et tenui stridente foramine longas

eiaculatur aquas atque ictibus aera rumpit.

Arborei fetus adspergine caedis in atram

vertuntur faciem, madefactaque sanguine radix

purpureo tingit pendentia mora colore.

Ecce metu nondum posito, ne fallat amantem,

illa redit iuvenemque oculis animoque requirit,

quantaque vitarit narrare pericula gestit.

Utque locum et visa cognoscit in arbore formam,

sic facit incertam pomi color: haeret, an haec sit.

Dum dubitat, tremebunda videt pulsare cruentum

membra solum, retroque pedem tulit, oraque buxo

pallidiora gerens exhorruit aequoris instar,

quod tremit, exigua cum summum stringitur aura.

Sed postquam remorata suos cognovit amores,

percutit indignos claro plangore lacertos,

et laniata comas amplexaque corpus amatum

vulnera supplevit lacrimis fletumque cruori

miscuit et gelidis in vultibus oscula figens

“Pyrame” clamavit “quis te mihi casus ademit?

Pyrame, responde: tua te carissima Thisbe

nominat: exaudi vultusque attolle iacentes!”

Ad nomen Thisbes oculos iam morte gravatos

Pyramus erexit, visaque recondidit illa.

Quae postquam vestemque suam cognovit et ense

vidit ebur vacuum, “tua te manus” inquit “amorque

perdidit, infelix. Est et mihi fortis in unum

hoc manus, est et amor: dabit hic in vulnera vires.

Persequar exstinctum letique miserrima dicar

causa comesque tui; quique a me morte revelli

heu sola poteras, poteris nec morte revelli.

Hoc tamen amborum verbis estote rogati,

o multum miseri meus illiusque parentes,

ut quos certus amor, quos hora novissima iunxit,

conponi tumulo non invideatis eodem.

At tu quae ramis arbor miserabile corpus

nunc tegis unius, mox es tectura duorum,

signa tene caedis pullosque et luctibus aptos

semper habe fetus, gemini monimenta cruoris.”

Dixit, et aptato pectus mucrone sub imum

incubuit ferro, quod adhuc a caede tepebat.

Vota tamen tetigere deos, tetigere parentes:

nam color in pomo est, ubi permaturuit, ater,

quodque rogis superest, una requiescit in urna.”

Desierat, mediumque fuit breve tempus, et orsa est

dicere Leuconoe: vocem tenuere sorores.